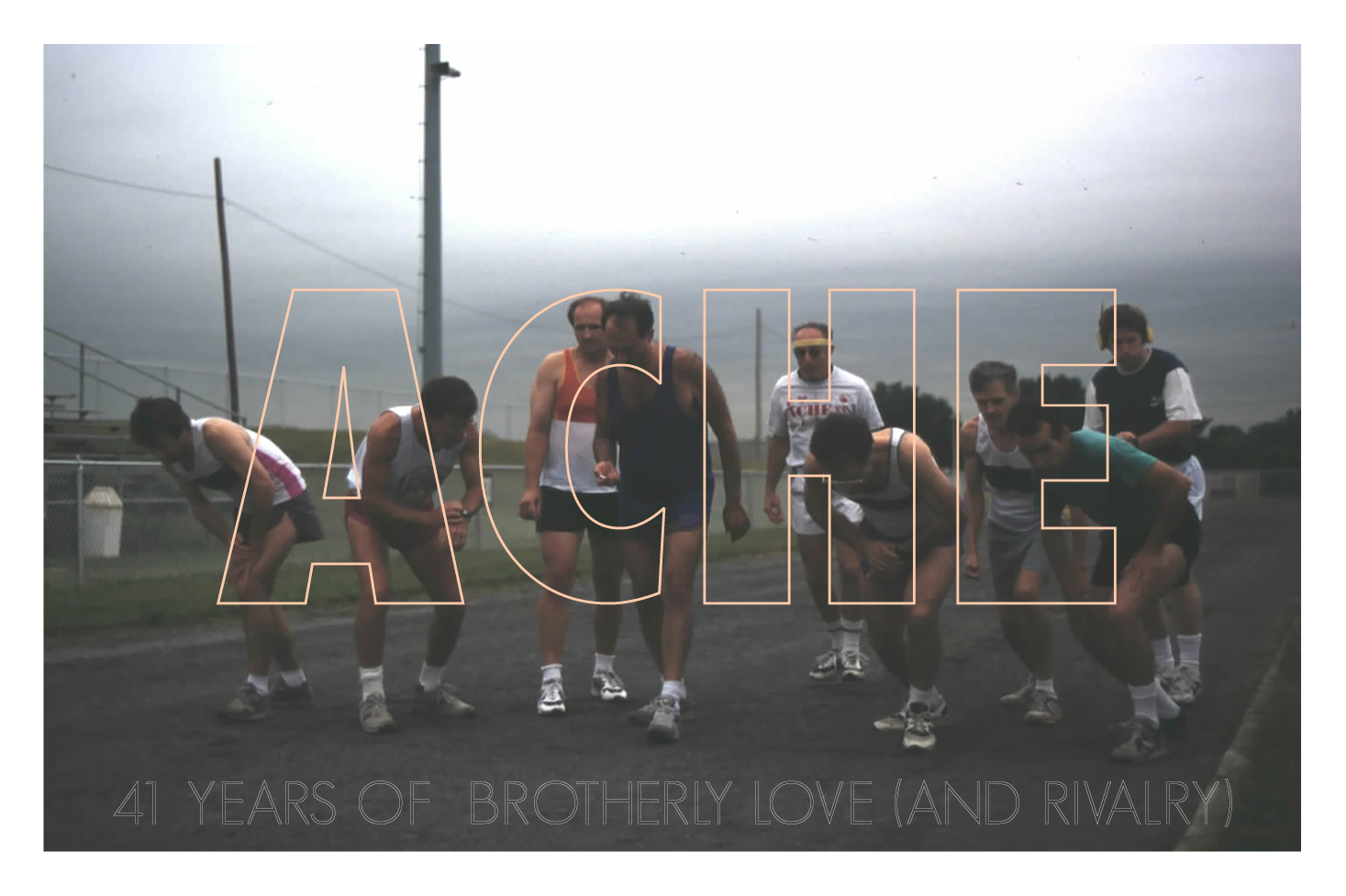

Ache (āk)

1. To suffer a dull, sustained pain.

2. To feel sympathy or compassion.

3. To yearn or long.

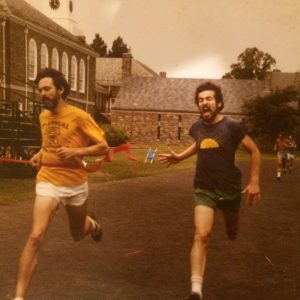

In 1976, my dad Tom joined ACHE, a D.I.Y. athletic tournament with events from bocce to basketball. Tom was a goofy, curly-haired hippy and the father of a 5-month-old baby girl. “I hadn’t started running yet and only had done sports as a kid.” Tom nervously propped up my infant sister in her baby backpack while he ran the 440-meter dash. He returned 90 seconds later to find the backpack tipped and my sister, Karrie, face down in the grass. ACHE, which stands for Athletic Competition of the Highest Echelon, was started by group of friends who met while studying to become Catholic Priests at a Seminary in Philadelphia. They all eventually dropped out. To blow off steam after their first year at seminary, the group biked 78 miles from Philadelphia to Sea Isle City, New Jersey. My dad was invited to join ACHE by one of its founding members, his older brother Joe. Tom says, “The motivation was just to have a fun weekend together. I don’t think anyone thought it would evolve into something that would last this long. After five years or so, most of the guys started to think, ‘Why not do this forever, or as long as we can?’”

In the 1970s, Philadelphia had some of the worst professional sports teams in American history. “Philadelphia” comes from a Greek word meaning “brotherly love,” but the city’s crude and unsportsmanlike reputation persists even today. Philly’s public image problem is perhaps best epitomized by an infamous ‘68 incident in which angry Eagles fans booed a Santa Claus and pelted him with snowballs during a halftime show. In the ‘90s, a courtroom and jail were installed beneath the football stadium. By the time the ex-seminarians established ACHE in 1974, they had embraced the anti-war, anti-establishment counter culture. Tom describes the main founder, Jerry McKendry, as a “high school athlete, a jock, great guy,” but the rest of them were products of the ‘60s, “peace and love” guys who thought being overly competitive was “not cool.” ACHE was a way to bring out the best in each other through competition, but at the same time, not look down on the “non-athletic guys.”

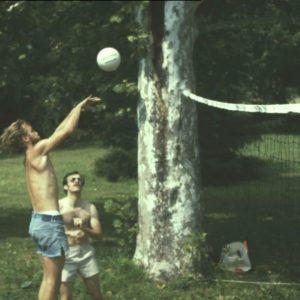

Events over the years have included football punt and throw, wall ball, bocce, softball, rowing in the Schuylkill River, a swimming relay race, soccer, ping pong, bowling, track, basketball and tennis. Each participant chooses 10 events, and scoring is weighted depending on the type of sport. The two lowest scores are dropped and the rest are added up before the final event: volleyball. The four competitors with the highest scores are split onto different teams. There is a lot of strategy involved in choosing the events, but many times the deciding factor comes down to that volleyball game.

Events take place throughout the city, some locations authorized, some not. One of my favorite events was the obstacle course at a bleak, bare-bones playground in North Philly. “The B and Olney playground was the epicenter of many of the guys’ athletic youths, so for years, we went back there for basketball and the obstacle course, which was a race through playground equipment. Up and down sliding boards, swing around climbing equipment, and underneath and around monkey bars.” Often there were kids playing. The ‘80s and ‘90s ACHE-ers, clad in unthinkably short shorts and sweatbands, were usually able to coax the kids off the “course,” by inviting them to watch the absurdist competition. One year, a random dog chased a participant in the middle of his time trial and he still ended up with the winning time.

During the ‘80s and ‘90s, a growing army of kids, many of them delivered by ACHE-er and midwife, Dick Jennings, helped keep score and carry equipment. To their children, these hairy, sunburned guys were Olympians. My dad was more of a joker than a varsity athlete, but training for ACHE had sparked a running addiction that eventually led him to run 10 marathons. Being one of the less athletic guys, he took advantage of aerobic sports that could be mastered through training like the mile run and the bike race. In group sports like basketball, he was often picked last. In ‘95, my dad found himself staring down the chance to win as he finally made it to the top four for the first time. He “came out of nowhere,” winning the mile run and the bike race, and lucked out being paired with ping pong ace Al Bergen. The underdog of the bunch, his team rallied behind him. My two younger siblings and I sat center court and flipped numbers on the scorecard. Watching the game, I willed him to win with the same focused magical thinking that I used to will the Phillies to the win the league championship in ‘93. A painfully shy kid eighth grader, I was filled with pride as his self-deprecating victory speech got big laughs. The next year, to “prove it wasn’t a fluke,” he miraculously won again.

Over four decades later, the 25 remaining members of ACHE are still competing with each other. Many of them still participate in the annual bike trip to the Jersey Shore, now joined by a pack of 150 others that includes wives, children and grandchildren. They keep in close touch, sharing personal news, inspirational quotes and inside jokes. More than ever they root for each other, always pulling for the underdog. Last year’s winner, Joe Fitzpatrick, a.k.a. “Mr. ACHE,” finally had his first chance at a win and many of his closest competitors were rooting for him. They’ve seen each other through marriage and divorce, children and grandchildren, and illness and death. When my dad lost his brother to melanoma in 2010, it gave me some comfort knowing Joe’s memory would live on with the entire group. Joe had an easygoing, wise way about him and my dad always looked up to him. Joe loved the bike trip most of all, and his four sons ride alongside my dad most years.

In characteristic unsentimental fashion, my dad kept very few pictures from his 40 years at ACHE. The photographs were mostly taken by his friend Forrest Lang, an ACHE member who once ran a marathon with a “Nikon strapped to his chest like Rambo.” The photos make me laugh, but they also make me think about the alternate meanings of the tongue-in-cheek acronym, of the dull, sustained pain of loss, of sympathy and compassion, of longing to win and longing to relive the carefree joy of youth. Exercise is the best defense we have against the physical and mental effects of aging, but I have a hard time finding inspiration in the often solitary pursuit of staying in shape. Maybe competition is the missing component. Maybe it’s a combination of brotherly love, the will to win, and an underdog mentality that causes some Philadelphians to care so deeply about the outcome of seemingly arbitrary sporting events. My dad and his friends in their 30s look so young, healthy and happy. My friends and I often complain about growing older, about aches and pains and missed opportunities. We’re too busy and we grow more distant. This summer during the 31st Olympics games, I propose we start our own athletic competitions. If we start now, we might be able to keep it up the next 40 years.

This article was originally published in RANGE Magazine Issue Four.

Images by Forrest Lang.

XX MOLLY GAVIN