On a blustery day in Alaska’s backcountry in 1960, Don Sheldon found himself in double jeopardy as two parties on Mount McKinley — originally dubbed Denali, or “The Great One,” by the Alaskan Athabascans — were in need of his unique search-and-rescue skills.

Mountaineer John Day and his crew were descending the mountain, the tallest in North America, following a historic push to the top of its South Summit. Somewhere around 17,000 feet, negations with a 500-foot cliff went sour and the entire team fell the length of the wall. Everyone in Day’s party was alive, but they were badly injured with broken, frozen limbs.

Over the next few days, Sheldon — a legendary bush pilot and outdoorsman — flew above the mountain, dropping supplies to Day’s team and depositing rescue climbers, who slowly made their way up the mountain to assist, at base camp. Army helicopter pilots attempted multiple rescues, but all failed due to their lack of knowledge of the mountain, electrical problems, wind conditions and terrain limitations.

Within a few days, Day’s party became a secondary concern as Helga Bading, a climber from Anchorage, developed a bad case of altitude sickness on Denali and was in dire need of evacuation. Sheldon and his skills were Bading’s only chance of survival.

Landing and takeoff at 14,000 feet were something no one except Sheldon would even consider. There were threats of oxygen starvation and dismal engine power due to thin air and sub-zero temperatures. Sheldon would need to land his plane on a 2,000-foot shelf positioned on a steep tilt. Should he overshoot, he’d fall ass over tea kettle. Should he hesitate, he’d slide backward into a jagged crevasse field. Then, assuming Sheldon landed successfully, he would need to reposition the plane so the nose was facing down the mountain for takeoff — all without accidentally pushing it off the mountain.

Adding to the agony, a severe storm loomed for more than three days and nights, stalling any and all flight plans. When the skies cleared, Sheldon jumped into his plane, ready to voluntarily serve above and beyond the call of duty — a trait that would become synonymous with his name.

Upon reaching Bading’s site on Denali, the famed pilot dropped a line of spruce limbs to mark the runway and indicate his height. Through a foggy windshield, Sheldon brought the 1,000-pound frame down like a feather. There was no time for celebration. Six climbers assisted the pilot in carefully rotating the plane for takeoff, loading Bading onto the plane and whisking her to safety.

Sheldon returned 18 more times, landing time and again on the continent’s highest airstrip to rescue the remaining climbers from Day’s party.

For Sheldon, this was simply another day on the job. He had the mind of a mad scientist, a heart of gold and the honor of a patriot who humbly served others. In his more than 30 years of flying, Sheldon never lost a passenger.

Sheldon grew up on a small ranch in Wyoming. By 12 years old, he’d lost both of his parents and moved in with his aunt and uncle. Upon graduating high school in 1938, intrigued by talk and stories from the north, Sheldon traveled to Alaska. In Anchorage, he worked at a local dairy long enough to pay for a one-way train ticket to Talkeetna.

He fell in love with Alaska, cultivating his comprehension of its rugged geography through trapping, mining, hunting, fishing and construction work. A job building an airfield and landing strip sparked his interest in bush planes, if only for the access they would grant him to the remote corners of Alaska. Sheldon studied engineering at the University of Alaska Fairbanks and then secured his private pilot’s license.

He jumped at every opportunity to fly and served 26 missions in World War II. During his tour of duty, Sheldon was shot down and survived two crash landings, earning him a Distinguished Flying Cross and four other medals. He saved most of his pay and, once discharged, purchased two airplanes. By July 1948, he was back in Talkeetna and anxious to start his bush aviation business.

Talkeetna was full of trappers, miners, sportsmen, homesteaders, geologists, surveyors and mountaineers, all in need of air service. Sheldon built an airplane hangar behind his house on Main Street and ran his business out of the entryway of his home. His wife, Roberta, assumed the role of business manager and booking agent. While Roberta rarely found a moment to herself due to a steady stream of clients, Sheldon was up in the sky with nothing but his own thoughts and the vast Alaskan wilderness — just the way he liked it.

From a nose-dive and subsequent remote rescue in an alpine lake, to a seemingly impossible rescue mission surfing the rapids of Devil’s Canyon on the Susitna River backward, to aiding climbers on Denali, at times in harrowing conditions, Sheldon’s life was colored by thrilling stories of adventure, service and the experience and expertise he cultivated in his own backyard.

In 1951, Bradford Washburn, director of Boston’s Museum of Science, came to Talkeetna in search of a glacier pilot to assist with mapping and photographing Mount McKinley. He immediately knew Sheldon was his man. Until then, the Alaska Range had never been mapped; it was virtually unexplored.

During the nine years Sheldon spent surveying with Washburn, Denali, which rises 20,300 feet above sea level, became a well-known freckle on the back of his hand. Once photos and maps were published, the mountain also became a hot topic within the climbing community.

In those years, the Great Gorge of Ruth Glacier, the world’s deepest glacier, and the mountains surrounding it became Sheldon and Washburn’s home base, where Sheldon came to master glacial landings.

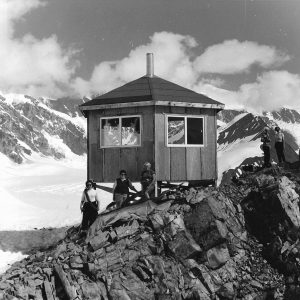

When a unique opportunity arose to homestead land near the national park’s border, this land — nearly five acres roughly 60 miles from Talkeetna — became Sheldon’s second home. Under his ownership, the space evolved into a base camp for adventurers. Perched on a rock outcropping made of iron and titanium, Sheldon built a mountain house.

He first made the hexagonal hut in his hangar in Talkeetna and disassembled it to fly it, piece by piece, to its current site at 5,850 feet on the Don Sheldon Amphitheater, formerly known as Ruth Glacier. The house sits among a scale so grand the human eye has trouble discerning height and distance. A mountain that looks like a quick snowshoe jaunt across the amphitheater may actually be five miles away. The space is flanked by rock faces that make the world’s tallest buildings look like anthills. Truly a place that can only be experienced firsthand, Sheldon desired to share the mountain house and its setting with all.

For Sheldon, a tremendous sense of responsibility accompanied this opportunity to host climbers and others. The pilot wasn’t one to drop souls off and wish them the best. He was truly an angel of the sky, at times watching over more than 20 different teams on Denali, checking their progress and looking for SOS messages stomped in the snow. He was known for dropping paper bags filled with stones and tied with red ribbon to inform teams of incoming weather or approaching predators. Occasionally, he’d also surprise and delight them with a gallon of ice cream.

Sheldon delivered a baby in the back of a single-engine plan, one hand on his controls while the other did as a doctor instructed through the radio. There was the time he waited out an 11-day storm in the northern tundra, tying his plane to frozen whale ribs so it wouldn’t blow away. He once narrowly escaped an avalanche by using its power to lift his plane’s tail as he took off. Sheldon often took it upon himself to help recover dead bodies from the mountain and scattered cremated remains in honor of those he knew and flew.

Sheldon was a luminary and a maverick, and Denali was his mountain. He loved people as much as he loved Alaska, ushering them through the air in his silver planes, so they could experience the grandest untouched terrain known to man. He built his reputation on good, old-fashioned service and gained recognition for understanding the intricacies of Denali better than anyone.

For a man who accomplished and witnessed countless “firsts” throughout his life, the impact Sheldon leaves behind is in the way he cared for and protected his community and made it possible for climbers to summit Denali, a legacy that continues to live on with every step taken toward its summit.

XX Whitney Connolly. 2019 Photos by Jeremy Fenske. Vintage photos courtesy of the Sheldon family.

Special thanks to the Sheldon family, Talkeetna Air Taxi, Roger Robinson and Joe McAneney for helping bring this story to life. This story original appeared in RANGE Magazine Issue 11: Origins. Order your copy HERE.