On August 20, 2014, the international scientific community issued a warning that Iceland’s Bárðarbunga volcano was most certainly going to erupt. I read the news while sitting at my kitchen table in Brooklyn, surfing the web as I finished breakfast and prepared to pack for an overnight flight to Reykjavik. The news of an impending eruption was so distressing that I panicked. I immediately ran into my bedroom, stripped down to my underwear, and lay on the floor, trying to breath normally.

Eyjafjallajökull, the last volcano to have erupted in Iceland in 2010, had filled the skies with foreboding ash, as if signaling the apocalypse. European flights were grounded for weeks. What would happen to Lauren and I on our trip? Would our plan to spend one week driving all the way around Iceland’s Ring Road be thwarted? Would we be stranded beneath an ash cloud that would block out the sun and choke us? Would we be forced to remain in Iceland for weeks until the skies cleared?

I stood up. I got dressed. Then I called every Icelander I knew. This meant my friend Holmar, and a woman on the help line at Iceland Air. Each took great pains to reassure me. Holmar said that if Lauren and I became stranded, we could stay with his dad, who would teach us to fish the old Icelandic way. The airline representative said calmly that there was no need to worry, as it was “only Mother Nature reminding us that she is there.”

Together, Lauren and I made a game-time decision to press onward. “This is our chance to go,” Lauren told me, “and we should embrace it.” To be completely honest, I wouldn’t have thought any less of Lauren’s character had she insisted we abandon our plans, and at the same time, I took strength from the sense of everyday courage that emerges when someone you love says, “Damn the volcano. Full speed ahead.”

And although I learned that sometimes what appears as a frightening disaster from afar is nothing more for the locals than the equivalent of a stalled subway train, the threat of Bárðarbunga still lingered throughout our trip. At every stop we had to regroup, check the latest volcano updates, and decide as a team to continue onward.

On the flight to Reykjavik, we hatched an idea that guided our entire trip. Together we would make a kind of creative travel diary. Every day, we would take a work break when Lauren, an MFA poetry student, would write, I would compose music, and we’d both take photos. In the end, we’d assemble everything we’d made as the collaborative account of two explorers. After a night in quaint, yet cosmopolitan Reykjavik, we drove south in case Bárðarbunga blew. Like so many visitors to Iceland, we’d heard fantastic things about the region and didn’t want to risk missing out.

We took our first work break in Reykjadalur, a steam valley. You trek over the hills, past windswept swathes of rolling earth redolent of Pink Floyd album covers, until you reach the valley where hot steam is misting up out of the ground and wafting gently away into the sky. It’s gently surreal, as if you have discovered a secret cove where clouds are made. Lauren found a rock and took out her notebook. I booted up my iPad and tapped out notes with nothing on my mind other than this strange and elemental scene. Nearby there was a flowing brook that was about 70 degrees Fahrenheit. After our session, we stripped down and went bathing.

Towards the end of our second day on the Ring Road, we arrived at Jökulsárlón, the famed glacial lagoon in the southeast. I say famed, although there’s absolutely nothing on site that would speak to its reputation. No gift shop, $5 valet or tour guides. Only a sign and a parking lot offset the awesome silence of the lagoon.

I felt deeply that this place was deserving of its own piece of music, if not a suite. As the glacier breaks off into the lagoon and floats out to the Atlantic, you feel like one of the gods, or in our case, like two of them, standing on the shore and contemplating the unfolding of nature, a cosmic process, the purest form of drama.

It’s no wonder that Iceland has become a magnet for adventurers, especially our sort: busy New Yorkers with a week off and a lust for remote places. Right between North America and Europe there’s this pocket of primordial earth, where in a real way you encounter water. And fire. And ice. Melting, freezing, erupting. A dizzying array of geological formations that result from something very hot meeting something very cold extremely quickly. It can make you feel like a primal ancestor of man, even if you’re driving a Volvo around the country and uploading selfies via a portable hotspot.

Lauren and I never shared our work during the trip. This wasn’t editing time. It was creating time, during which each of us gave the other space to pursue our imagination. We wanted to see what new combinations would appear afterwards back in Brooklyn and not interfere with the moment.

Bárðarbunga continued to threaten, increasing its alert level every day, yet we kept agreeing to press onward. We stayed a night in the eastern fjords, where the water has carved into the greenish rocky earth, and everything is misty and nautical. I found a cultish sculpture made of a dozen antlered skulls piled in a hole. At a refurbished sea house, we dined on reindeer meatballs and fermented shark.

Heading west, it seemed like we suddenly left the planet. We crossed into the highlands, a barren and uninhabitable zone that constitutes the bulk of Iceland’s interior. I kept a lot of Floyd and Eno on the car stereo. The ground and the mountains turned red, drained of all color or signs of life. I wrote a piece, “Highland Raga,” to imagine melodies that would drift unimpeded across that vast terrain.

As a creative person, I’m seduced by possibility. I love exploring what could be rather than what is. Sometimes this makes composing hard. There’s a fork in the road and both choices are great. When I composed music in Iceland, I was limited to the place I was in and the iPad I had brought. Iceland encourages creativity because it’s where the Earth itself is most violently creative, the island’s surface expanding with the lava that cools after every eruption.

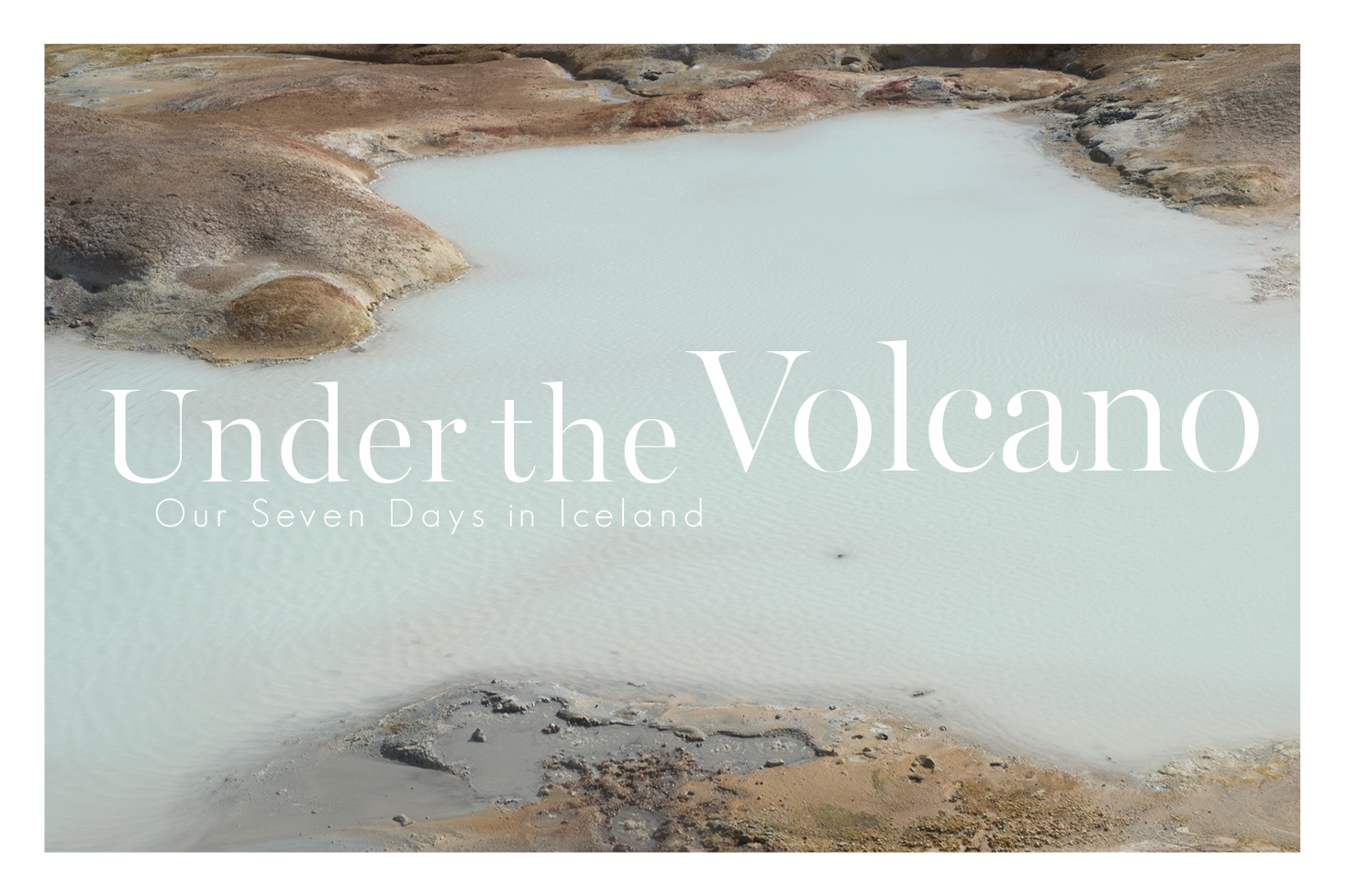

We arrived at Krafla, the volcanic fields just east of lake Myvatn, and its neighbor Hverir. We saw cauldrons in the ground where the Earth was still bubbling into being. Afterwards, Lauren wrote, “This is the part of the Earth they forgot to finish.” It made us think of Mars. During a work session in Hverir, we watched fellow sightseers pick their way among steaming hot mud pools while the smell of sulfur hung heavy in the air.

In the Myvatn region, the eggy, devilish odor of sulfur is everywhere, even in the water, and it reminds you that the ground beneath you is cooking, as if you are standing on the surface of a cosmic oven. If the lid is too tight and the pressure is too high, the whole thing can blow — melt a glacier, spew ash, or ruin your entire summer vacation.

The eerie feeling of visiting Mars on holiday continued on our hike from nearby Dimmuborgir. The hike solidified for me how the experiences of being in love and of being a pioneer can tightly intertwine. What do we know of love, anyway, if we can’t test it on unfamiliar ground? That day, we climbed a steep volcanic crater. On the ridge, we were almost blown off by a pounding wind. Lauren grew scared, and as we locked arms, I shouted instructions on how to brace against the gale. We made it down the slope, and then turned to see a much older couple behind us in sturdy outdoor wear, holding hands and strolling on the ridge as if in Central Park.

Back in Bed-Stuy, in the apartment where Lauren and I would soon live together, we spread all our pieces across the living room floor: the poems, the music, the photos. We edited. We debated. We revisited each moment of the trip and threaded our way through shared memory, finding correspondences, creating new associations. There was the Iceland we had seen together, a new cartography that we had begun to trace.

This article was originally published in RANGE Magazine Issue Four.

Images by Lauren Roberts and William Raunchier.

WILLIAM RAUSCHER

___

William Rauscher is an electronic musician and the editor of Material.fm. His project with Lauren Roberts about Iceland can be seen at rrrr.material.fm. William also composed an audio track during his time in Iceland, which can be found here.